Last time I wrote about the very apparent gap between reality and changes in football when it comes to Fan Engagement (‘Fans: Football ignores the new normal at its peril’).

In it, I asked the question, ‘Why do I detect an atmosphere of ‘business as usual’ from much of the industry? Why is it that fans seem to be absent from all sorts of discussions raging on about the future of the game? It’s particularly noticeable when it comes to both the ‘when’ (streaming & kick-off displacement) and the ‘where’ (games abroad).’

This gap is no better demonstrated by the failure of football to finally respond to years of sharp practices over broadcast agreements, specifically so-called ‘kick off displacement’.

Kick off displacement is essentially what happens when a broadcaster decides that it wants to broadcast a match at a time other than the actual scheduled kick-off time of the match (e.g. 3pm, 7:45pm). Everyone accepts that part of the deal when it comes to the financing of the modern game is that some matches will be broadcast, and that this at times necessitates games being moved.

In fact, at the time of writing the Telegraph broke the news that the Premier League (EPL) was considering a new set of matches to kick off at 18:30 on a Sunday. More on that later.

A brief history lesson

Arsenal v Arsenal Reserves might not sound like a particularly inspiring fixture for anyone except the most obsessed of Arsenal fans, but that was the first live match broadcast by the BBC in the 1937. Some years later, a short-lived contract was signed between ITV and The Football League (EFL) in the 1960s which fell because clubs wanted more money. (“Some things never change” I hear you say!) Subsequently, highlights programmes with regional broadcasters were the mainstay of football (except for the World Cup & FA Cup) on the TV until early 1980s.

A short-lived contract was signed between ITV and the EFL in the 1960s which fell because clubs wanted more money. (“Some things never change” I hear you say!)

Since the 1980s, apart from the odd hiccup, live broadcast matches have become part of the fabric of the game, first on terrestrial (ITV, BBC), and subsequently satellite and non-terrestrial TV. The important caveat to that is the ‘3pm blackout’, successfully lobbied for by then Burnley chairman, Bob Lord, in the early 60s. This rule prevents domestic matches being broadcast between 2:45pm and 5:15pm on a Saturday with only a few exceptions made for international weekends.

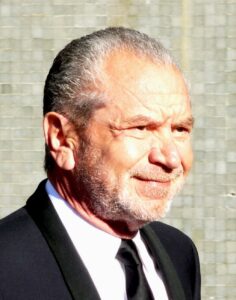

What really began to glue football (and sport more generally) and broadcasting/TV together was The Premier League, which in many respects was a three-way creation of broadcasting, technology and sport. In fact, to illustrate the point about technology, Alan Sugar, then owner of Tottenham Hotspur was also owner of Amstrad, which manufactured set-top boxes for the nascent broadcaster. He has since admitted that he improperly intervened in the bidding process, enabling Sky to submit a bid that trumped ITV’s. Not only did he benefit directly from the growth of the satellite broadcaster, he eventually even sold Amstrad to Sky in 2007.

The Premier League was in many respects a three-way creation of broadcasting, technology and sport

Although the breakaway league’s proposed partnership with TV was famously driven by the broadcaster ITV (via then ITV Chairman Greg Dyke), Sky was the end beneficiary. As a result, from the very start the notion of it being a broadcast event was baked in. It’s no surprise that broadcasting continues to drive the EPL.

It’s pretty much a given that the reason that broadcasting deals have almost exclusively grown year-on-year is that the EPL hasn’t been riding a wave generated by sport alone, but a cyclical one driven by changes in technology that make sport both more monetisable and more widely available, driving the takeup of the technology, and thus revenues.

It’s one of the reasons that I’ve always poured cold water on the idea that the boom will eventually bust under its own imaginary steam. The almost relentless growth will only cease – or at least slow significantly – when the technology dictates that it will. Unofficial Partner’s recent series on piracy is quite good on this, and seems to suggest that we could already be seeing signs that sports rights in some cases are already slowing significantly.

Streaming and streaming platforms & technology are now very dominant drivers of change in the industry. With international rights now beginning to outpace domestic ones and broadcasting on multiple devices now the expectation, there are so many additional markets to exploit and additional revenue streams to mine. Because we expect to be able to witness every bit of history being made, video in particular has become central to everything we do and are as humans. We no longer have to describe seeing something, we share the footage. Whether it’s the latest training ground action, or people dangling helplessly from a cable-car in Pakistan.

Streaming (or ‘Over The Top’ (OTT) services that can be watched via services like Netflix) has also made most content available at any time. It’s meant that sport is one of the few forms that survives as ‘event viewing’ that can be watched together. It wasn’t that long ago that we sat down and watched everything at a set time. Now, as happened with the written word becoming democratised, we can access this stuff ourselves with minimal gatekeeping, and so events – one offs like football matches or sport more generally – have become much more valuable.

Streaming has helped create the creeping idea that there is a ‘right’ to access matches live

What streaming has helped create in English football is the creeping idea that there is a ‘right’ to access matches live. Because of that, so the logic goes, we either have to displace kick-offs, or we have to accept that the 3pm blackout should fall as a result. This despite the fact that the ‘product’ – The EPL – is atop a pyramid of tens and hundreds of other clubs, all fighting to rise up the pyramid to compete at the highest level possible.

It’s the popularity of football in England that has helped to create the conditions that mean fans want to access these matches come what may, a dynamic that has been sped up by the naturally limited availability of tickets to attend matches, as well as the actual price of the tickets – which have been made eye-wateringly expensive by the clubs.

Combine that with the fact that not all matches are broadcast and this means a lot of drivers creating demand. Coupled with the pressure of the ubiquity of video content, this means that streaming almost becomes a go-to option – legal or illegal, it doesn’t matter. We’ve all seen pirated content on social media channels, either filmed from the stadium by a user, or clipped from the live stream.

As my last article was saying, there is a problem with many of those in the game and advising clubs at the moment, in that they still don’t appear to have grasped that we are going to have an independent regulator for football, and that secondly, culturally, clubs are now expected to listen, absorb and change their decisions as a result of dialogue with fans. The issues between broadcasters as a driver of revenue and clubs on the one hand, and fans as the key consumer of the game itself on the other, are a precise example of where this change has seemingly not seeped into the minds of enough of these people, and it’s a real problem.

Culturally, clubs are now expected to listen, absorb and change their decisions as a result of dialogue with fans.

Except it’s not a problem of the broadcasters. They want to put things on to drive viewership, either because they sell the programme individually, sell subscriptions, and/or sell advertising. Why would you expect them not to ask for the most they can possibly have?

The problem is the clubs, and by direct association, the leagues & competitions themselves (EPL, EFL, FA Cup) Why? Quite simply, if someone asks me as an individual to do something that I do not want to do, I don’t do it. I can’t blame someone else for forcing me to drink that second pint. It’s not the car’s fault that I got into the driver’s seat when I knew I was over the limit, and it’s not the fault of the police when they stop me, and it’s not the fault of the judge or magistrate who sentences me to a driving ban. I made bad decisions at the start of the process, which meant that other bad things consequently happened, and I can’t claim otherwise.

Clubs have their own decisions to make about how they position themselves when it comes to broadcasting, and then collectively, to agree to deals. Think about it this way: If an arms manufacturer offered a record-breaking sponsorship deal for The EPL, temptation aside, I very much doubt that anyone would be rushing to sign them up. Conversely, The EFL’s charitable partnership with the British Red Cross was signed up to because the clubs agreed that it would be reputationally beneficial to them to do so.

If an arms manufacturer offered a record-breaking sponsorship deal for The EPL I very much doubt that anyone would be rushing to sign them up

The key word here is ‘clubs’. The clubs, we are told repeatedly, are the owners or members of the competitions. They are bound by collective agreement – especially in broadcasting matters – and they ultimately make collective decisions.

As we now know to our detriment, this collective structure was what allowed a self-serving attitude to prevail over the sensible approach that regulation shouldn’t be delivered by the regulated. That’s why the independent regulator is coming.

I still think that far too many people who should know better are enabling the clubs to hide behind the broadcasters (maybe the broadcasters are content to allow this as part of the exchange, maybe not), whilst others genuinely think it’s the fault of the broadcasters themselves for being ‘greedy’. Whatever it is they’re not being honest about what we need to do to change this direction of travel.

Both of these perspectives are lazy, and an abdication of responsibility. We are talking about the English pyramid of football. That either means something or it doesn’t. We cannot defy gravity: We are not the NFL, NBA, MLB, and we cannot compete on that basis. Football is not a closed system. It is a multi-layered pyramid that clubs only reach the top of if they achieve sporting success, and clubs are sporting, business and community assets, not a group of franchises awarded to the highest bidder or the region that the competition wants to expand into, and fans sit within that environment.

Clubs, EFL and EPL, FA, don’t have to sign up to the terms laid out in every contract they’re handed by the broadcasters… clubs make choices, leagues follow policy informed and shaped by those choices, and broadcasters operate in that context.

So what? The point is that the clubs, EFL and EPL, FA, don’t have to sign up to the terms laid out in every contract they’re handed by the broadcasters. If a broadcaster demanded that a match be played at midnight, although I don’t doubt someone would be singing the praises of such a forward thinking move, it’s highly unlikely that it would happen. The point is that clubs make choices, leagues follow policy informed and shaped by those choices, and broadcasters operate in that context. Fans are being squarely placed outside of this equation for no good reason except that the people who make the decisions don’t want to be challenged on it in such a way that might mean they have to stop, in which case the money might not arrive in quite such large quantities. It’s hardly about turning the taps off.

And if activist fans want to stop the slew of changes to kick-offs, they need to change the target of their ire. It wasn’t the fault of Rupert Murdoch that clubs broke away and formed the Premier League. It was the decision of clubs and the abject failure of The FA to either put in place proper guarantees to ensure they kept the competition reined in, and to share the proceeds of growth, or even block the move.

It wasn’t the fault of ITV Digital that clubs signed up to a broadcasting deal that didn’t contain adequate protections against failure, and which instead of acting as rocket fuel to the nascent business model, ended up being more like a cup of cold sick, causing the near-extinction of multiple clubs and the loss of at least one in May 2002 in less than ideal circumstances. It’s not the fault of broadcasters that they use football to increase viewership to their platforms or channels, and in doing demand that huge numbers of fixtures are displaced to suit their programme schedules.

It is the clubs. The clubs are the ones who sign-up to the deals. The clubs are the ones who want the money to pay for a new left-back or salary increase for their striker. The clubs are the ones who don’t insist on having a clause in the contract to prevent last minute changes, or limit the number of matches broadcast and therefore, number of kick-off displacements, or even demand standard compensation for their fans when such displacements cause fans to have to cancel expensive travel plans.

The clubs are the ones who don’t insist on having a clause in the contract to prevent last minute changes, or limit the number of matches broadcast.

So what’s the choice? Or is it really a ‘Hobson’s Choice’? There’s always the argument which goes like this: “Do you want to have a smaller wage budget and less chance of signing the best players?” I’ve heard this repeatedly when ticket price rises are in the offing, or the cost of a pint goes up in the stadium, and if I was presented as arguing that I want football to earn less from broadcasting, I would expect someone to parody my argument in that way.

Except that whilst I have some sympathy with the idea that no club is going to hamstring themselves by deliberately cutting their wage bill in half to fund cheap burgers, it’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about being true to what the game and clubs are: not shiny entertainment complexes, or solely old museum pieces covered in dust, but living, breathing, and venerable sporting institutions with fans part of that.

If the ‘dash to dialogue’ that football has been making means anything at all, then it also means that fans should be able to help to shape decisions like those around broadcasting contracts.

Having happy fans who aren’t protesting or angry with you is always preferable. Not only that, and this is the most important message I can give to clubs, the EPL and EFL: if the ‘dash to dialogue’ that football has been making means anything at all, then it also means that fans should be able to help to shape decisions like those around broadcasting contracts. Otherwise dialogue just means ‘only the things we think you should be able to influence’, and that’s not dialogue. It’s just things you’re prepared to involve them in.

My message is this: pick up the phone to the FSA as the body that represents the interests of fans across the country. Ask them in for a conversation about kick-off times before this next set of rights is sold. Try to work through a plan that maybe offers something for fans. Offer to insert a clause in broadcasting deals that limits the right of broadcasters to displace kick-off times. I’m not saying none at all, but I am saying we should limit them because the system is skewing too far one way – away from the fan that is part of the reason broadcasters want the rights.

Pick up the phone to the FSA as the body that represents the interests of fans across the country. Ask them in for a conversation about kick-off times before this next set of rights is sold.

Clubs have to understand that the era we are headed towards, if not now in, is going to be more regulated, and the expectations from fans is that they are involved directly in shaping decisions that directly affect them.

They absolutely want to have good leaders of their clubs, who make good decisions and anticipate their needs in advance. But one of the ways that clubs become much better anticipators of what fans want is by involving them in decision making, dialogue, at different points of the decision making process, and not just at the end when they’re told that they can’t expect more than a handful of Saturday 3pm kick-offs because another package of matches has been sold with a new kick-off time.